CMS - A Vibrant Thread in the Fabric of Chicago History

By Patrick Butler

1850: Chicago’s population was 28,269; the city limits ran from the lakefront to North Avenue, Wood Street and 22nd Street (now Cermak Road); James Curtiss won a second one-year term as mayor; Alan Pinkerton opened his detective agency, becoming the nation’s first ‘’private eye’’; and gas lighting made its debut here on Sept. 4. On Oct. 21, the City Council passed a resolution urging disobedience of the federal Fugitive Slave Act; and Congress approved land grants for what eventually became the Illinois Central Railroad.

1850: Chicago’s population was 28,269; the city limits ran from the lakefront to North Avenue, Wood Street and 22nd Street (now Cermak Road); James Curtiss won a second one-year term as mayor; Alan Pinkerton opened his detective agency, becoming the nation’s first ‘’private eye’’; and gas lighting made its debut here on Sept. 4. On Oct. 21, the City Council passed a resolution urging disobedience of the federal Fugitive Slave Act; and Congress approved land grants for what eventually became the Illinois Central Railroad.

First class letters cost five cents to mail. (They would go down to three cents the following year and stay there for about 20 years, when postal rates would be further reduced to two cents.)

California had just been admitted to the Union, and James Harrison and Alexander Twinging just invented the refrigerator.

The Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (the nation’s first all-female training school for doctors) opened that same year; and Dr. David Jones Peck graduated from Chicago’s own Rush Medical College, becoming the first black American in history to receive an MD degree.

Of course, back in 1850, you really didn’t need to go to school to become a doctor. And since 1826, you didn’t even need a license to practice medicine in Illinois.

Enter the CMS.

|

|

Dr. Levi Boone - |

On April 19, 1850, a group of doctors concerned about the anarchic state of their profession met with Dr. Levi Boone to found a local medical society to battle quacks, raise standards of medical education, and promote public health.

These were not easy tasks at a time when there were at least 17 different kinds of ‘’doctors,’’ ranging from homeopaths to uroscopians on the loose here, to say nothing of all the folk practitioners who claimed to be able to erase a baby’s birthmark by rubbing it with the hand of a corpse!

Whooping cough, it was believed, could be cured by tying a bag of bugs around the patient’s neck, if the patient preferred not to eat ‘’the cast off skin of a snake or eggs obtained from a person whose name had been changed by marriage.’’

Even the ‘’regular’’ doctors were a mixed bag at a time when you could still get an MD degree from any number of correspondence schools. Indeed, of the 33 medical schools asked to report on their educational standards to the American Medical Association in 1849, only nine required students to actually spend time in a hospital as part of their training.

At the same time, some segments of ‘’establishment’’ medicine were so enamored of academic discussions for their own sake that the Illinois State Medical Society, also founded in 1850, was forced to pass a resolution the following year requiring all clinical lecturers at the group’s conventions to focus on "practical subjects,’’ rather than ‘’pure theory.’’

For one thing, few doctors had the time in those days.

Most had sidelines like the stagecoach line operated by Dr. John Temple when he wasn’t seeing patients.

Boone himself not only served as mayor, but was a part-owner of a railroad with medical partner Dr. Charles Dyer, also a sometime conductor on the ‘’Underground Railroad’’ who in 1848, had been beaten up-for assisting a runaway slave.

While president of Rush Medical College, Daniel Brainard himself ran for mayor several times; in 1849, Dr. Graham Fitch, a professor at Rush, got himself elected to Congress; another Rush faculty member, obstetrician Dr. John Evans, was appointed governor of Colorado Territory for his role in helping Abraham Lincoln get the 1860 presidential nomination.

Dr. Joseph Goodhue, who died after falling into an open well while making a night house call, is credited with helping to set up the city’s first public school system.

Dr. John Egan, who had come to Chicago as an Army doctor in the early 1830s, also sold real estate and patent medicines—including the Sarsparilla Panacea touted as ‘’the most perfect restorative yet discovered for debilitated constitutions and diseases of the skin and bones.’’ Dr. Edmund Kimberly augmented his thriving practice with a pharmacy, while also serving as Chicago’s first village clerk. Later, Kimberly would get one of his business partners elected to the state legislature to look after Kimberly’s canal interests.

At the same time, some of Chicago’s pioneer doctors also used whatever political muscle they had to promote overall public health—with varying results.

In the early 1850s, Dr. Nathan Davis, chairman of a CMS committee investigating basic sanitation in Chicago, warned that houses were being built too close together, and not just in slum neighborhoods. Women and children, he added, were five times as likely to get sick as men who were more likely to go out at night, even if only to the corner bar.

Garbage was still being thrown into the river or allowed to fester in fetid alleys, prompting Dr. Davis to campaign almost single-handedly for a sewer system.

Only a year before Dr. Davis’ report, a cholera epidemic brought here by an immigrant ship, the John Drew, killed one out of 36 Chicagoans.

Malaria was so common it was considered almost a rite-of passage for newcomers. Typhoid and pneumonia ran so rampant an 1854 visitor was surprised to find Chicago ‘’not as unhealthy as had been supposed.’’

Of course, even the doctors didn’t always know who died of what, giving rise at times to some incredible diagnostic flights of fancy. In 1851, for example, five Chicagoans supposedly died of ‘’decline’’; two from ‘’delirium’’; and one from a ‘’visit of Providence.’’ The following year, 15 people were reportedly done in by the ‘’effects of traveling.’’

Small victories did come, however, slowly, in the war on killer epidemics.

By 1855, doctors were empowered to post quarantine warning signs on the homes of smallpox victims. And in at least three city wards, local option votes evidently made it illegal for residents to keep hogs in their homes.

Thanks to the continuing efforts of groups like CMS, Chicago had no serious cholera epidemics after 1866. By 1890, all of Northern Illinois was malaria-free.

But as homes became safer, the workplace grew more dangerous than ever. Accidents and job-related illnesses skyrocketed after 1875, with more than half Chicago’s population working in factories and slaughterhouses.

But it was foul odors rather than concern for workers’ welfare that prompted city authorities in 1877 to clean up the Stock Yards.

While checking out the city’s 74 slaughterhouses, Health Commissioner Oscar De Wolf found only 11 of 292 rendering tanks had any ‘’apparatus’’ for suppressing the resultant ‘’pungent, acrid and horribly fetid gases.’’

Unfortunately, when DeWolf filed charges against several of the meat packers, juries--mostly rounded up in saloons near the Stock Yards--instead censured DeWolf for harassing legitimate businesses.

City authorities responded in 1879 by requiring that all slaughterhouses be licensed and subject to minimal health regulations. Scandals continued until at least 1889, however, when DeWolf’s successor, Swayne Wickersham, cracked down on the sale of diseased cattle with the collusion of city officials.

Discussing ‘’Packing House Wounds’’ at a CMS meeting in the early 1880s, Dr. William Axford may have been the first prominent doctor to address the dangers of infection caused by cuts from knives that had been contaminated by diseased cattle.

At about the same time, the Board of Health began inspecting "manufacturies’’ as well as packinghouses, and found some of the worst conditions in the near West Side garment industry.

But it wasn’t until 1907, following publication of Upton Sinclair’s ‘’The Jungle’’ and a series of federal investigations ordered by President Theodore Roosevelt, that a full-scale Department of Factory Inspection began enforcing health and safety laws and cracking down on Chicago sweatshops, especially those using child labor.

Despite Dr. Davis’ early efforts, an 1881 house-to-house check of one ward made up mostly of immigrant-filled tenements turned up 18,976 people living in 1,107 mostly one-room hovels that were sometimes so cramped there wasn’t even enough standing room for the entire family.

No wonder so many of the men practically lived in the taverns, DeWolf concluded in one of his reports.

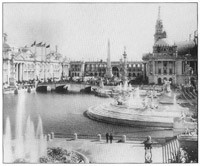

The situation hadn’t improved much by 1891, when typhoid killed at least 2,000 Chicagoans. During the Columbian Exposition two years later, which was supposed to have showcased the city’s achievements since the 1871 fire, a visiting Englishman described Chicago as ‘’the queen and guttersnipe of cities, cynosure and cesspool of the world.’’

The U.S. Labor Commissioner wasn’t much kinder the following year when he pronounced housing conditions here to be the worst of any major American city, with only 2.8 of all slum dwellers having their own toilets.

Another safety nightmare was public transportation, which was even then trying to cut costs wherever it could. To save on conductors’ salaries, for example, the privately- owned transit companies refused to add extra cars even during rush hours, forcing numerous commuters to ride on the outside steps and hope they weren’t thrown to the pavement by a sudden stop.

The result from streetcar falls as well as factory accidents was a "multitude of mutilated people’’--and a thriving prosthetics industry.

Most, of course, were treated at County Hospital, which by the 1870s had become overcrowded and rife with such corruption that one medical journal of the time described County as ‘’an almshouse for the scum of the party which got beaten in the local election.’’

In 1876, the liquor bill for County Hospital was about half what was being spent for medicines; almost twice that for patients’ clothing and bedding; and three times what was being spent for surgical supplies.

By 1888, the CMS was characterizing several of the less-distinguished staff doctors at County Hospital as ‘’a collection of servile tools of the vilest political ringsters.’’

Although Dr. Christian Fenger had to borrow money to buy his job at County, others-- like the apparently more clout-heavy Dr. James Herrick-- had only to send ‘’an annual note of thanks and a box of cigars ‘’ to their sponsors.

County’s shortcomings, plus a flood of immigrants and others with special needs prompted different religious and ethnic groups to start caring for their own.

St. Luke’s was started by an Episcopal pastor to provide a "clean, free Christian place’’; Michael Reese opened as the city’s first Jewish hospital in 1882; The German Hospital started the following year but changed its name to Grant Hospital during World War I; In 1889, St. Mary of Nazareth opened to serve a growing Polish community, while Norwegian-American began serving new Scandinavian arrivals five years later.

In 1896, the Alexian Brothers, a Catholic religious order founded in the 13th century to care for Black Plague victims, opened a hospital in what is now the posh Lincoln Park area to serve needy men, especially those injured in industrial accidents.

|

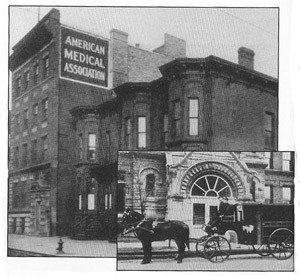

| Headquarters of the American Medical Association, 1905. Inset: Presbyterian Hospital ambulance, 1904. |

Illinois Masonic was founded in 1921 as a refuge for indigent Masons, while Martha Washington Hospital’s original mission was the ‘’reclamation of alcoholic, opium-addicted women.’’

In 1865, Dr. Mary Thompson founded the Chicago Hospital for Women and Children as a ‘’home’’ for the ‘’respectable poor in need of medical and surgical treatment.’’

In 1931, there was even a maternity hospital for ‘’mothers of Catholic families, of white race, living in legitimate wedlock, and whose husband’s income is less than $2,000 a year.’’

Those who didn’t meet all those requirements could always go to the Salvation Army’s Booth Memorial Hospital, or to County, which by the turn-of-the-century was cleaning up its act and fast becoming one of the most respected teaching hospitals in the city.

In 1937, the first blood bank anywhere in the United States was started there by Dr. Bernard Fantus. Thirty-one years later, Cook County Hospital again broke new ground with the creation of the nation’s first trauma center, designed to give specialized treatment to accident and violence victims.

By the early 20th century, CMS had again shifted its attention from epidemics and industrial accidents to the battle against quackery and ‘’irregular practitioners.’’ A public relations committee was mobilized to lobby for pure food and drug laws and against patent medicine advertisements in newspapers.

Tuberculosis could be avoided with Dr. Jayne’s Expectorant; Dr. Sweet’s Infallible Liniment cured sprains and sore muscles; for teething infants, there was Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup (found to contain a gram of morphine per ounce of liquid).

Elderly people with ‘’sour’’ or ‘’thin’’ blood were urged to clean out their systems with Wishart’s Pine Tree Cordial; and every kind of ‘’lameness’’ (as well as cancer and ‘’old ulcers’’) could be cured with Dr. Plumleigh’s Indiana Botanic Plaster.

A ‘’Professor Silliman’’ of Yale College touted the restorative powers of Old Sachem Bitters and Wigwam Tonic; while assorted lawyers, politicians and even some clergymen preached the virtues of Dr. Ford’s Pectoral Syrup.

Since the mid-19th century, however, doctors were also often as much at war with other practitioners, (homeopaths, chiropractors, osteopathic physicians and even Christian Scientists) as they were against political corruption and patent medicines.

But as early as 1848, Brainard himself admitted that ‘’it is impossible not to see that homeopathy (a then very competitive school of medical thought based on the idea that the smaller the dosage, the more effective the drug) is but a reaction against the excessive use of drugs.’’

Twenty years later, a CMS member lamented that ‘’The people of these days prefer quacks to the regular members of the profession.’’

Nobody argued with the man.

Treatments of the so-called ‘’irregulars’’ were seen by much of the public as a lot safer than some of the mainstream remedies--such as the copious quantities of mercury administered for malaria that instead sometimes poisoned the patient.

Or the calomel dosing that often led to tooth loss--causing more than one early Chicago doctor to spell it out right on his shingle: ‘’Dr. John Smith. No Calomel.’’

As recently as the early 1900s, however, the training of even the so-called ‘’regular’’ doctors was still so spotty, Illinois, with its 15 mostly substandard medical schools, was dubbed ‘’the plague spot of the country’’ by medical education reformer Abraham Flexner.

Flexner’s 1911 report commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation drove a number of the worst ‘’diploma mills’’ out of business, while encouraging the better schools to enact even more stringent requirements.

In 1918, for example, Rush gave senior students the choice of a year’s hospital internship or a fifth year of classroom work.

That same year, CMS helped provide health care at no charge for the needy families of servicemen off fighting the First World War. CMS also helped arrange free physicals for school children.

But at the same time, there were segments of organized medicine gearing up to fight what they considered undue "outside interference’’ and the erosion of ‘’free choice’’--even if it meant letting homeopaths and other ‘’unorthodox’’ practitioners ply their trade.

As far back as 1858, the Chicago Medical Journal warned that "much as we are scandalized by the widespread medical quackery of our time, we would do well to adhere to our democratic notions of government--giving the fool full liberty to preach folly and his followers abundant permission to follow him.’’

In that spirit, some doctors as late as the 1870s even opposed quarantine as an unwarranted infringement on personal liberty and ‘’commercial intercourse.’’

Whether anyone liked it or not, however, quarantine became the rule during the 1918 influenza epidemic that left 381 Chicagoans dead in just a single day, Oct. 17.

During the two-month crisis that killed 8,510 here, health authorities not only quarantined whole apartment buildings when necessary, but outlawed spitting on the street, holding public funerals and smoking on streetcars and L trains.

Friends were encouraged to salute rather than shake hands, and anyone sneezing or coughing in a public place was immediately asked to leave.

Influential segments of the profession also campaigned against health insurance and free or government-run clinics serving any but the most destitute. In 1935, a CMS committee recommended adopting what many considered a far too flexible formula (based on cost of treatment, the patient’s income and family responsibilities, etc.) to determine eligibility for ‘’charity’’ or "state medicine.’’

Dr. Edward Oschner, on the other hand, argued that any man earning $100 a month, with a wife and three children, should be able to pay his own medical bills.

In the end, neither recommendation was adopted by CMS or anyone else.

Actually, government funding was nothing new to the profession. In 1833, Dr. Edward Kimberly was treating Indians in his office and sending the bills to federal authorities.

Organized medicine, however, was not only divided over who should pay whose bills, but was occasionally at odds over which diseases should be treated at public expense.

|

|

The Columbian Exposition, 1893. Medical and related exhibits were shown in many buildings. The site is where the Museum of Science & Industry now stands. |

Shortly after his appointment as Chicago health commissioner in 1922, the respected Dr. Herman Bundesen faced a firestorm of protest when he proposed distributing condoms in public washrooms, drug stores and even brothels--and setting up city-funded clinics to treat venereal diseases.

The Illinois Medical Journal called the idea ‘’revolting," while it condemned Bundesen’s ‘’outrageous and unlicensed exercise of power.’’

‘’God forbid that above the Stars and Stripes any misguided theoretical radical shall ever place the Flag of Priapus and the bar sinister of the phallic symbol,’’ prayed the Chicago Medical Recorder.

Ironically, it was Bundesen’s much-better received infant welfare program that cost him his job, at least temporarily.

His massive parental education program led to a reduction in baby deaths from 89.3 per thousand in 1921 to 63.8 in 1927, the year Bundesen was forced to resign because he wouldn’t include Mayor ‘’Big Bill’’ Thompson’s political literature along with the infant care information the Health Department had been distributing to all Chicago mothers.

‘’Big Bill’s‘’ heavy hand, incidentally, fell even harder on Dr. Theodore Sachs, director of the city’s first tuberculosis sanitarium, who committed suicide in 1916 to protest the mayor’s political interference.

Bundesen ran for coroner shortly after being forced out of the Health Department by Thompson, and was back at his old job in 1930 when Democrat Anton Cermak replaced Thompson as mayor.

By 1936, Chicago was reporting the lowest infant mortality rate of any major American city. Bundesen remained health commissioner until he retired in 1960.

After World War II, CMS again found new battles to fight--this time pressing the city to buy more Fire Department ambulances. CMS wanted 20 but the City Council drew the line at five in 1948.

In 1956, CMS was honored at its annual convention by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis for ‘’working day and night to inoculate enough of the city’s population to avert a full-scale Polio epidemic."

Over the years, in fact, CMS meetings have often reflected and even anticipated continuing trends in both health care and American life.

Today’s health consciousness, for example, may be traceable to a 1957 CMS clinical convention at the Palmer House where Dr. Paul Dudley White, President Dwight Eisenhower’s physician, began spreading the gospel of healthy eating and vigorous exercise.

By 1970, CMS members were getting an update from Dr. Patrick Hughes on ‘’Drugs, Youth and Protest,’’ while eight years later CMS convention attendees were paying an extra $100 to get Dr. William Masters’ take on ‘’Human Sexuality.’’

A year later, CMS--like the rest of the medical community--was abuzz with predictions that tuberculosis would be eliminated in the United States by the year 2000.

Not only did that prediction prove premature, but by 1989 the CMS was offering a special program on how to deal with a whole new medical nightmare--AIDS.

The topic was repeated again in 1993.

The following year--at the 50th annual clinical conference at the Sheraton-Chicago Hotel-- history of an entirely different sort was made when Sandra Olson became CMS’ first woman president, heading the largest county medical society in the United States with more than 10,000 members.

One can only guess what Dr. Levi Boone would have thought.

Patrick Butler is a Chicago journalist, columnist, and a former political editor.

Document Actions